Midnight Mass (part three)

Part 3: Necrofascism

We couldn't talk about religious extremism in the United States without going here, could we? No, we couldn't.

I'll start this session by going back to Beverly Keane, a character who I've only talked a little bit about so far, but who's pretty dang important from the second episode onward. Basically, you know the crazy church lady from "The Mist?" Well, she's back, and she's...I was going to say "crazier than ever," but I'm not sure if that's actually true at all. If anything, Keane might be a smarter, saner, more self-aware version of the character. Either that, or her self-deceptions have become so intricate and sophisticated that they've gained their own sentience, and it's smarter than she is.

As aforementioned, she was one of the biggest advocates for taking the not-actually--good settlement from the oil company, and some of that money seems to have vanished while it was bouncing around between organizations she had a management position in. She built a rec center attachment/outbuilding thing for the church, but no one can tell how much that actually costed her, and with the town losing its young people and not producing many more children it barely gets any use anyway. She likes being able to see it, and having everyone else be able to see it whenever they come near the church, though. She's single, possibly widowed, possibly not, but either way it's an anomaly for her age and culture that's never quite addressed.

Her establishing character moment comes early on, when - after complaining about remorseful town drunk Joe Colley's dog barking at her too aggressively and being politely told by Sheriff Hassan to go Karen somewhere else - she resorts to sneaking the dog rat poison (pet murder! Another King Bingo check!). At the island's Ash Wednesday potluck, when his tearful breakdown over the dying canine can be seen by everyone and maximize his humiliation.

On account of his maiming of Leeza years ago, Joe is socially isolated, drunk and unruly enough to easily hold in contempt, and in general an easy target. Meanwhile, I don't believe she actually thought that the dog was a danger to anyone.

Joe tells Hassan that he suspects her of killing the dog, but he has no proof and little credibility. And, when Hassan does try to press Beverly on the subject, she very carefully, very deniably implies that if she were to accuse him of (accidentally or otherwise) poisoning the dog, the community would likely believe her over the Musim outsider whose authority everyone resents.

It's a very tightly written scene. She's really careful with her wording.

She latches onto "Father Hill" almost from his first day on the island, and doubles down on it once his sleight-of-hand charisma and eventual healing miracles turn him into a literal cult figure. She appoints herself his unofficial manager and right-hand woman. And, when the town's renewed religious fervor is at its highest, makes a point of handing out bibles at school seemingly for the purpose of antagonizing Hassan when his son brings one home. A PTA meeting gets called, and there's another uncomfortable dialogue between Beverly and Hassan with a few others chiming in.

There are some context clues that point to this show being set a few years before its date of release. Early 2010's-ish, I'd say. In this scene though, while they do include some contemporary conservative bad faith arguments ("teach the controversy" etc), I swear the writers also managed to work every single last MAGA shibboleth into Bev's lines. All "easily offended" this, and "burning books and censoring free speech" that, all while working in minor digs about Islam that just barely fly under the radar of most of her audience (and actively appeal to some of them who are simply too polite or too afraid of the sheriff's authority to say what she's saying). The show couldn't have her rant about "wokeness" without muddling the time period, but she says it in spirit.

As a teacher, Erin is present for the meeting, and is one of the few who speaks out in agreement with Hassan. She's in the extreme minority though, with Riley's parents being among Bev's vocal supporters. It isn't long before Bev kinda sorta admits that the rules don't matter anymore now that they have a Christian priest performing miracles right in front of their eyes, and when Hassan expresses some orthodox Muslim scepticism toward miracles he gets even more pushback for being a buzzkill.

...

I said I'd talk a bit more and a bit more critically about Hassan and Ali earlier, and this seems as good a place as any. I really wanted to like Hassan, but his story just doesn't ring true to me.

According to the autobiography he provides in episode 6, Hassan was a promising young NYPD officer who eagerly joined the counterterrorism task force after 9/11. He thought he was perfectly placed to show that Muslim Americans are a good minority. When they started spying on mosques and immigrant community centers, Hassan provided his cultural and linguistic knowledge to the investigations. Then they started setting quotas for Muslim arrestees. Making a point of entrapping Muslims for things like drug possession in order to turn them into unwilling spies and snitches. As an NYPD detective, Hassan was presumably A-Okay with doing this to African Americans, but when his own people started getting the treatment he realized that it was wrong. As soon as he gave the department the slightest bit of gentle pushback, he and several other prominent Muslim officers were promptly thrown onto backwater night-beat duties and watched like hawks both at work and while off duty. His wife urged him to bear it with dignity, but when she then died to pancreatic cancer he left New York in a cynical rage and...brought his teenaged son to a tiny, dying island town in the middle of nowhere to get away from the bad memories and racism.

Creator Mike Flannegan is a lapsed Catholic. He knows Catholicism, he knows American Christianity, and he knows what it's like to be on the right and wrong sides of both. He's not a member of an immigrant minority, though, and it shows.

You're trying to tell me that this man responded to bigotry by taking himself and his son away from any sort of community they might have had, and moving to an isolated hamlet full of nothing but (almost all white) Christians?

Away from any other Muslims? Away from any other Pakistanis? Really?

If he was offered a big sum of money to do this on a *highly temporary* basis until they could find another sherif, I could maybe buy this. That doesn't seem to be the case, though. As it is, Hassan trying to escape persecution by moving away from anywhere that had his own people in it and surrounding himself and his poor son entirely with the persecutor culture just...the show does treat this as a terrible mistake on his part, and one that made his son suffer for no good reason, but I have trouble believing that it's a mistake he would actually make. A white Christian or maybe even Jewish American might do this in response to grief and frustration. A brown-skinned Muslim American would not.

So, while I like the idea of Hassan and Ali, and the role they play in the story is a fairly important one, the entire time that they're onscreen I'm just asking myself "why are they here?"

...

Subtextually, this scene calls back to some earlier things. The resentment of the distant government that makes them follow its laws without protecting their livelihood and health. Of the mainland environmentalists and nonchristian police who should have no business telling them how to live their own lives. Of their own children, leaving them to rot in rural disintegration while they run off to bigger, better, smarter things. Of how they're more willing to give a pass to people like Bev Keane or the oil executives, since they're not the ones putting themselves in the way right at this second and also gave them the appearance of nice things at some point in the past. And also, implicitly, because Bev is one of them, and the visible parts of the oil company are made up of working people "like them."

In one of the last optimistic scenes of the series, in early episode 4, Riley's father - after encouragement from the priest - confesses some of these feelings to him, and begs his son's forgiveness. He'd always had a resentment for his son acting like he was too good for this island, or too smart for this rural bluecollar religious culture, even when he was a kid. Then he wasted his shot at actually putting his alleged smarts into practice, and costed his parents a ton in legal fees right when they could least afford it. His father had a lot of reasons to dislike him by the time he got out of jail, some of them reasonable, but others very much not so.

There's forgiveness, reconciliation, and understanding.

Until Father Pruitt has to lie to Riley about why Joe hasn't made it to their latest AA meeting, and Riley happens to have learned some recent personal details about Joe that let him see through the lie. Then Riley is a troublemaker again.

...

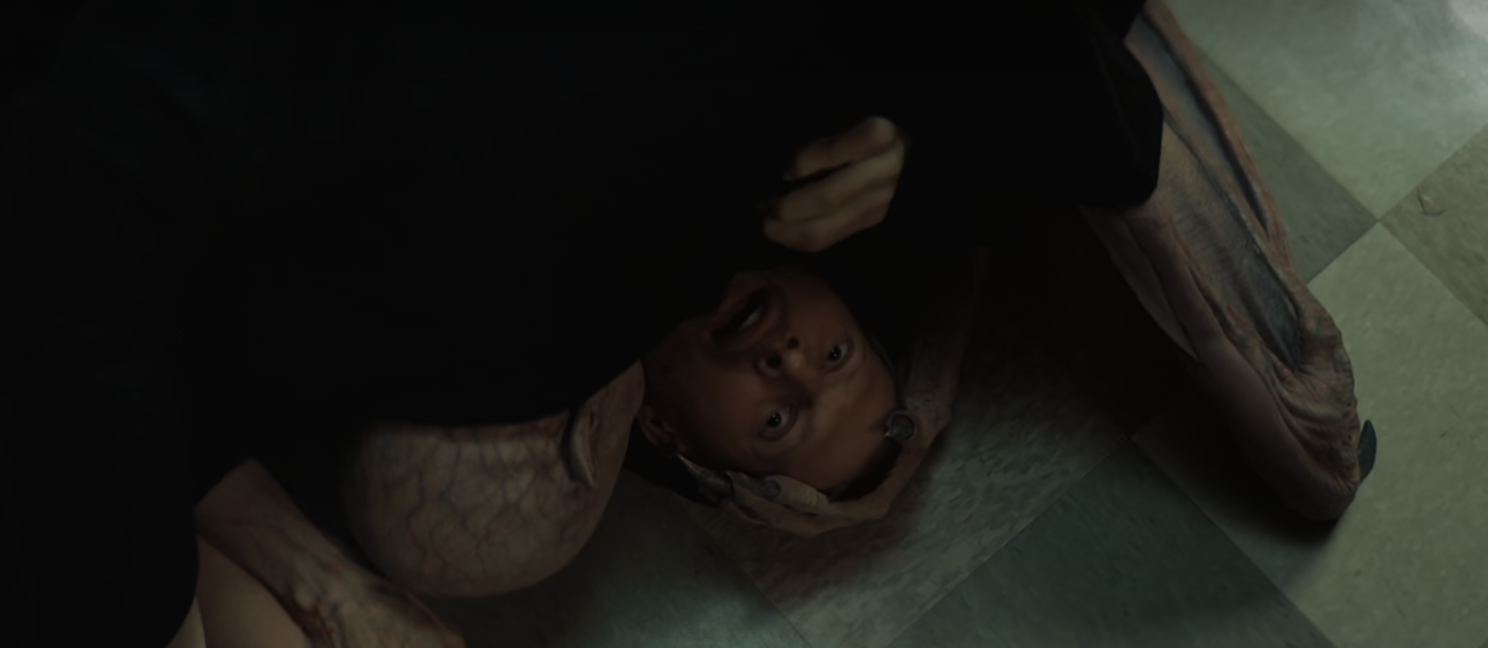

The morning after the killing of Joe Collie, Bev walks in on Pruitt curled up next to Joe's exsanguinated corpse, blood all over his face, whispering to himself over and over again about how he doesn't know what came over him, he doesn't know why, he doesn't understand. Traumatized to near-catatonia by what he just did in the throws of vampiric hunger. Bev has almost no reaction whatsoever to Joe's death. And immediately starts thinking of how to clean Pruitt up and get him awake and presentable in time for morning mass. And then of how to explain things away to the parishioners when he explains that he's allergic to sunlight now.

The impression one gets is that she thinks killing Joe is something any ordinary person would want to do, and that his death and Pruitt's complicity in it need no explanation or commenting on. It's like she's from a world where this happens every couple of days.

She also seems to have already had a plan in mind for disposing of a body. Certainly, it didn't take her any apparent time or effort to formulate one.

Pruitt is totally frozen with horror after committing murder and cannibalism. In this state, he's very suggestible, and willing to latch onto any explanation offered to him. So, when Bev reassures him that Joe was the worst kind of sinner - a degenerate, a drunk, a blasphemer, and the maimer of an innocent child - and that it only made sense that Pruitt's latest fit of divine ecstasy would drive him to execute the guilty. Jesus came to bring not brotherhood between men, but a sword, after all. She quotes (and hilariously misquotes, in some cases) a bunch of cases of God killing or ordering the killing of various sinners and heretics throughout the scripture. Even peacemaker Jesus himself chasing the launderers out of the temple with whips, etc. When the mayor and the town handyman show up to ask where the priest is, Bev is able to browbeat them into compliance as well, and enlist their help in corpse disposal while she gets Pruitt cleaned up and cheered up.

It should be noted that we briefly saw Bev take out the rat poison again after the dog murder. I think the implication is meant to be that since Joe realized that she was the one who did it, she figured it was a matter of time before he acted against her, so it was best to make it look like the drunk poisoned himself before then. Certainly, it would explain her preparedness for exactly this turn of events, if Pruitt had actually just spared her the trouble.

The next time we see Pruitt at the pulpit (for evening mass, this time. Henceforth he'll only be holding services at night on account of his recent health issues), he's changed. Before, he seemed like a more passionate and charismatic than average priest, with some shades of evangelical Protestantism creeping in once he started with the faith-healings and promises of immediate reversals of fortune and such. Now it's like he's a completely different person, in both message and in delivery.

For the message: I actually hadn't seen this scene yet when I wrote the "church of christ the vampire" mini-essay at the end of the last review, so I was both taken aback and proud of myself when he repeated some of the things I said in it almost word for word. About the importance of suffering, the aspirational position of Jesus' crucifixion, about the need to do horrible things if God demands it, about the rightful damnation of the unworthy, the transubstantiation of evil actions into holiness through blood and grace.

For the delivery: I really have to admire the actor's performance in this scene. He speaks passionately, but he also gets lost and starts mumbling and seeming to forget where he is once in a while. Interrupting sentences with other sentences, circling back to the same points over and over again, etc. There's a lot of nuances that the actor has to juggle here, and he does a superlative job of it. It's clear from watching that 1) Pruitt is still dwelling on the murder he committed the other day and can barely concentrate on the here and now, 2) Beverly wrote most of this speech for him, and he didn't go over it quite enough times before trying to pass it off as his own, and 3) he's trying to convince himself of the monstrous words he's saying while play-acting as his usual, more resolute, self. The delivery communicates all these causal factors, while also managing to make the effect of them be that Pruitt hits the *exact same* spiralling cadence and rambling semi-coherence as a Donald Trump speech. In a way that couldn't possibly be unintentional by the creators.

His audience consists mostly of frustrated, older, rural people who feel left behind. Slighted. Looked down upon. And they've just been given an extra infusion of energy in the form of vampire blood, along with validation that their beliefs are right and everyone else's are wrong in the form of the healing's "miraculous" presentation. People who - for a number of interrelated reasons, some justified and others not - resent their children, resent the laws, resent the foreigners. Suddenly they feel like everything can be good again, if they just fly the flag and march in the parade and await the saviour's next commands.

Even though their town is still just as dead and rotting as it was before. They feel the difference inside of them.

...

The night after he tried and failed to tell his parents (well, his mother is somewhat receptive. Ish) that Pruitt is lying about Joe's whereabouts, Riley decides to confront Pruitt about it. On one hand, given the nature of his suspicions, one might question Riley's decision to go do this alone at night in Pruitt's church. On the other hand...Riley is a young, athletic man who pumped a lot of iron in jail, and everyone thinks that Pruitt is sick, so I can perhaps forgive the overconfidence.

Unfortunately for Riley, he picked the same night that the "angel" chose to return to Pruitt and help him restock his dwindling supply of communion wine.

It turns out that Pruitt has been loaning the angel his old cloak and hat to hide itself from casual viewers when it wants to go outside. The "ghost of Father Pruitt" that Riley saw in the rain that first night was actually the angel taking a beachside stroll after wiping out the island's feral cat population.

Anyway.

It doesn't appreciate being walked in on. And, while Pruitt would have preferred to talk Riley down and send him away if at all possible, his master doesn't give him the chance to. And Pruitt doesn't try to argue with it; he just stands by, closes the door to make sure no one else happens by, and (we later find out) even sipped a bit of Riley's blood that the angel didn't finish.

I didn't expect this to happen at the end of the fourth out of seven episodes. But, it turns out we haven't quite seen the last of Riley yet. The way vampirism works in this show is apparently more complicated than it first appeared.

The angel's own motives are likewise more complicated. Well, sort of.

There was an analysis I read a long time ago, I wish I could remember by whom, about the archetype of the "night-demon" in folklore and mythology. It's a weird, nebulous category of mythical creatures that happen to share a number of associated traits. Nocturnal. Elderly, either in appearance or in fact. Associated with deep water or the underground. They tend to drink blood or drain life energy. They tend to target children or young people. They tend to be undead or undead-adjacent.

The dead consuming the living, an inverse of the natural process of decomposition. The old consuming the young, an inverse of the natural process of childbirth and parenting. They come out at night, when the sun is asleep, God isn't looking, and the natural order can be challenged. When children are found missing the next dawn, it's a victory of the night over the day, the past over the future, that which should be dead over that which should have gotten to live.

These creatures are more often than not female (Lilith, Lamia, etc). Part of that might be a product of ancient misogyny, but part of it might also be that it just strengthens the metaphor. An old woman eating children and aging backward. Opposite-childbirth. Anti-life.

...

More than one political theorist has described fascism as "death-worship."