Midnight Mass (part two)

Part 2: the Church of Christ the Vampire

Vampires have been many things in many cultures. In this post, I'm talking specifically about the modern euro-american version of them - the one that was codified by 19th century gothic novelists and run with by modern fantasy/horror authors - when I say that vampires are anincrediblyChristianmonster.

In some respects, vampires are literal "antichrists." They cannot cross water, and they immerse themselves in soil. They're kept down for good by an impaling wooden instrument, but can get back up from almost anything else. They tempt mortal men and women into all manner of depravity and sin as a means of control. Most obviously, they turn the central conceit of Christian salvation on its head; as Christ gave his blood to grant mortals eternal life, vampirestakethe blood of mortals to grantthemselveseternal life.

The weird thing, though? In other respects, vampires are less like opposite-christs than they are like christs played straight.

They emerge bodily from their tombs, often restored to the prime of youth and physical health (this is notably NOT how vampires worked in most pre-19th century stories). They attract small, secretive groups of followers to whom they grant a share of the magical power they wield. Oneveryimportant detail that seems to have been invented wholecloth by Bram Stroker and then copied by many others is that in order to procreate, the vampire needs to feed a victim some oftheir ownblood in return. The inversion of Christ's blood sacrifice - the taking of blood from victims to extend the vampire's unlife - now comes packaged with areenactmentof that sacrifice - the initial giving of blood that creates a new vampire. It is literally the gift of divine blood, drunk by the supplicant, that allows them to emerge from their own tombs and live eternal lives with eternal youth.

Given how many vampiric traits are the literal opposite of things Jesus did, it's awfully strange how this incongruously Jesus-likeaspect became such a widespread part of the mythos. I don't know if Bram Stoker was thinking along these lines when he invented this detail for "Dracula." If you want an alternate explanation, Stoker was writing right at the time period when epidemiology was coming into its own, and the sharing of fluids starting to be acknowledged as a prime disease vector. Vampires have been associated with plague since long before their Christianization, so it may be that Stoker was just working in some contemporary anxieties about infectious disease. The way that itcaught on, though? I don't think that the disease subtext is all there is to it. Especially in light of how important boilerplate Christian imagery has also become in the vampire subgenre during the same time period.

And yeah, like I said, we going "Salem's Lot" now too.

...

Over the next handful of nights, more people - including both Riley and Erin - catch glimpses of the uncanny, twitching figure in the night. Nobody tells anyone else, of course. The sightings were brief enough that they all just decide they must have been seeing things. Then one night, a week or so after the cats turned up dead in the water like the Gerasene pigs, that drug-dealing ferryman is lured into an empty house and never comes out again. He's not local, and he's not popular among anyone besides his teenaged customers, so it's a long time before anyone even thinks to look for him.

That's around the same time that the miracles start.

First, claiming to act on a sudden compulsion, Father Hill raises the communion wine up in his hand and tells the handicapped Leeza to come and get it. To her own surprise as much as anyone's, Leeza stands up out of her wheelchair to take it.

A spontaneous neural regeneration. Such cases aren't unknown. But for Father Hill to have had that strange, semi-ecstatic fugue come over him and tell her to stand up, when there's no way he could have possibly known? That says miracle.

He experiences a health problem of his own after doing this. He has to run off to the bathroom to cough up blood for a bit. But still, he healed a paraplegic.

The town experiences an out-and-out religious revival in the wake of this incident. More healings take place. Riley's father's back is better. His mother's vision improves to the point where she doesn't need her glasses anymore. Every mass is packed with virtually all the remaining islanders going forward.

But it doesn't work out well for everyone.

During his AA meetings with Hill, Riley remains firmly doubtful despite the mounting evidence of supernatural providence. Part of this is down to simple applied scepticism, but some is theodicean. One injured girl got miraculous healing, and some other people are being cured of various aches and ailments. Okay, that's nice and all, but why would God heal the members of this one random little island town and not everyone? How come Leeza gets her spine repaired, but the girl who Riley hit with his car still bled to death in front of his eyes? The best that Father Hill can tell him is that, well, God works in mysterious ways. He pretties it up and makes it sound more sophisticated, but that's what it basically comes down to.

Joe Collie, the drunk who caused Leeza's injury, starts coming to the AA meetings as well. He and Riley, who both accidentally ruined young lives while drunk, have a lot to bond over. Despite the well-read young man and the provincial old fisherman-turned-town-drunk having so little in common on the surface, they end up becoming close friends.

But, Riley still doesn't get it. Why did God heal Joe's victim, but not his own? Leeza has her own (very intense) scene where she comes to Joe's trailer, excoriates him for ruining her life in a single moment of thoughtless fumbling, and then tells him that if God can undue her injuries and seemingly reverse at least some of the harm, then she can find it in herself to forgive the sad, remorseful old man. That's great for her, and for him. But Riley still doesn't get it.

Things get downright bleak for Sheriff Hassan and his son. Already on the margins of the community due to their religion (and, less overtly, their ethnicity), they find themselves totally cut out of any and all sense of community in the town's Catholic revival. When the ambiguously corrupt city council woman Beverly Keane (who also is the school administrator. And the church organizer/assistant. Yeah, she's that kind of smalltown oligarch) uses the occasion to start handing out bibles in school, the vast majority of townsfolk side with her over the Muslim father who's son is being preached to on the state's dime. Teenaged Ali ends up starting to attend church and take communion against his father's wishes, out of sheer desperation for social inclusion.

I'll talk much more about Hassan, Ali, and Keane (including the PTA scene in particular) in the next part. For now though, I'll just say that Hassan is living a nightmare and Keane is using her adjacency to the church to benefit from Father Hill's miracles.

Then, Erin. Pregnant schoolteacher Erin, who is just starting to get over her trauma as she reconnects with Riley and prepares for the personally redemptive task of parenting. With the way things are going between her and Riley, it's starting to look like she might not have to be a single mother after all. Until her pregnancy disappears.

No discharge. No miscarriage. She just isn't pregnant anymore.

When she goes to the mainland to get another doctor's assessment, she's told that there are no signs she was ever pregnant in the first place. The doctors there are more willing to believe that she's having a mental breakdown than that she was seven months pregnant until a few days ago.

Miraculous. But she really, really, really didn't want this miracle.

...

Throughout the second and third episodes of "Midnight Mass," the story is punctuated by a flashback sequence. Well, actually an ongoing framing flashback sequence that contains other, smaller flashbacks within it. The framing scene is Father Paul Hill during his first night on the island, having a midnight confessional session by himself in the empty church. He has committed - and will continue to commit - the sin of deception, though it is for the greater good. He must lie to all the people of Crockett Island, at least, for a time, in order to eventually bring them both truth and salvation.

The old priest, Father Pruitt, is not in the hospital. He did not fall ill during his Israel trip, at least not precisely.

Pruitt was more senile and out of his head than anyone on the island had been willing to admit to themselves. After visiting Jerusalem, Pruitt joined a tour group up the Damascus Road, along which the apostle Paul is supposed to have had his revelation and change of heart. In a bout of dementia, the elderly priest wandered away from the group into the desert, and a freak sandstorm prevented anyone from going after him by the time he was missed. Caught in the storm, Pruitt took shelter in an ancient ruin that had seemingly just been unearthed by the wind. In the darkness of the ruin, he caught glimpses of a creature with gleaming eyes, sharp movements, and a tall, writhing silhouette.

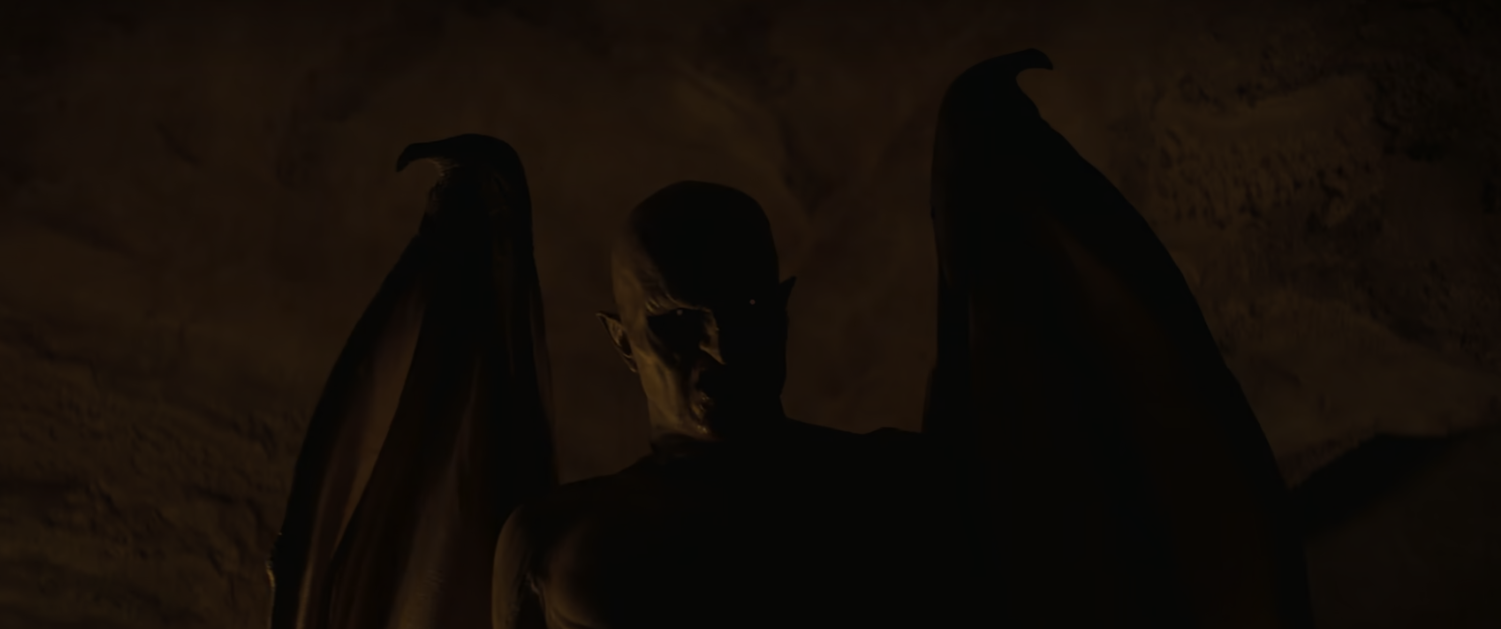

When it came into the light of the matches he fearfully lit...eh, well. Okay, I'm gonna have to criticize the production for a bit. When we see this thing lurking in the darkness or obscured by sand or mist or whatever, it looks terrifying. They gave it this Nosferatu-like silhouette and uncanny, twisting motions that just...look, have you seen "The Babadook?" If you've seen that movie, then you'll know exactly what I'm talking about. The thing is, when the creature comes into the light and has to be played by a guy in a costume, it's hard for me to believe that they're actually the same monster. And the dark, claymation-y version of it is way scarier.

I feel like they should have waited until the final episode or two before showing it up close like this. It would have preserved a lot more dread and tension for a lot more of the series. But, back to the story.

Father Pruitt was lost in a haze of dementia to begin with. The anaemia he suffered when it tore his throat open and sucked out his blood probably also didn't help his perceptions of what happened. The part he remembers most clearly is when the creature offered him a drink of its own blood in return, and he felt the pain and frailty melting from his body like wax before a flame. His mind was clearer than it had been in years. His body healthier than it had been in decades. He knew what he must have just experienced; the true blood of Christ, carried to him directly by an angel. What of it if the angel was a hulking corpse-thing with bat wings that manhandled him? There's ample biblical precedent for angels having monstrous appearances and alarming demeanours.

As for its fear of sunlight, well...eh, must be some weird quirk of this one angel's.

Father Pruitt knew immediately what he must do. He remembered his congregation, getting older and sicker on a forsaken prison of an island, who had done nothing to deserve such a sad fate. He knew that the true, untransubstantiated blood of Christ must be brought to them as well; why else would Pruitt, out of all the priests in the world, have been chosen for this blessing? Perhaps the rest of the Church will follow eventually, but the ailing fishermen he left on Crockett Island must be intended to receive it first. Otherwise, why would it have been him?

Father Huitt was one of the oldest residents of Crockett Island. Barely anyone still alive remembers what he looked like as a young man. He took on the name "Paul Hill" and returned to them, planning to reveal the truth to them in stages so as not to cause alarm or attract unwanted outside attention. The Angel seemed to approve of this plan; after all, it willingly climbed into that box so he could bring it with him during the day. It's also been making blood donations for him to mix into the communion wine.

...

Early in the second episode, one very old, senile townswoman sees "Father Paul" and identifies him as Pruitt. It's dismissed at the time as her being senile and thinking anyone in a priest uniform is Pruitt. In reality, she recognized him from how he looked when she was a young woman herself.

The strange intimacy. The way that Paul so quickly earned the trust of all the islanders, including Riley. He already knew all of them, and they didn't know that he knew them.

All that charisma. All that uncanny speed for learning names, faces, problems, and desires. He was cheating.

...

Some time after the healings really get underway, the priest suddenly has convulsions and dies in the middle of a conversation with some other islanders. He then comes back from the dead after his heart had stopped beating, again, before their eyes.

The process of vampiric transformation happens a little differently in this series than it does in most. It's almost like a kind of "reverse disease." Drinking vampire blood heals and rejuvenates the body. After you've been consuming it for enough time, your body reaches a state of readiness. Perfect young adulthood with perfect health. Then the random convulsive episodes start. Eventually, one of them kills you, and then you get back up as another vampire. The wings, presumably, take longer to grow in.

After his resurrection, Pruitt finds himself burned by sunlight, repulsed by food and drink, and drawn to the scent of blood.

...

Erin's body doesn't seem to have known what to do with the pregnancy while in the process of restoring itself to prime vampirization state. So, it ate it. There's a truly painful scene where she and Riley discuss the afterlife, and how unborn babies fit into it if it indeed exists. She surmises that God must have sent this innocent soul down to simply sleep in the comfort of the womb for a while without ever having to wake up. Just a nap. Up in heaven, it will have the life that it didn't get on Earth. A life that, when she describes it - perfect young adult youth, eternal companionship with her friends and family - is actually a predictor of her own state once she turns. The baby who she's imagining for it got eaten, by her, because it was in the way.

...

A few nights later, in a one-on-one meeting with Joe Collie, Father Pruitt cracks his head open and drinks his blood off the floor while Joe slowly bleeds to death right next to him.

Pruitt was just pretending to be acting on a strange, seemingly divine, compulsion when he commanded Leeza to stand up out of her wheelchair, when in truth he simply knew that the "angel" blood in her communion wine must have healed her by now. When he attacks Joe, the priest really is following an ecstatic compulsion that he doesn't understand.

The angel hasn't been appearing to him at night lately. Presumably, after it ate that drug dealer, it needed to fly to the mainland for a while to find other victims who won't be missed. It comes back soon after this incident, though, and it's confident feeding will get much easier very soon. For itself, and for its prospective small army of spawn.

I'm going to say some very controversial things now. Before I do so, I want to clarify that these are not neccessarily things that I personally believe. Rather, they are things I've been told by ex-Catholic friends, some of whom were very deeply versed in Catholic theology and doctrine before their lapsing. I don't know enough about Catholicism to say how valid or how historically justified these criticisms are. I just know that there are people within the Catholic church who have anxiety about them, and that horror fiction is often as much about those little nagging doubts as it is the obvious fears.

So.

...

Within Roman Catholicism, the church is said to be "the body of Christ." It's something that's said and paraphrased often and in many different ways throughout Catholic worship.

The most important ritual in Catholicism, the one that must be performed most frequently, is communion. The consumption of the body of Christ. Both the church membership and the communion meal are referred to as "corpus christi."

...

A usually-unspoke theme within Christianity in general and Catholicism in particular is the divinity of suffering. Back when Christianity was a minority religion being persecuted by Roman authorities, this sort of belief would be a pretty natural fitness adaptation. But what happens when this religion later comes into power itself?

It's sort of a weird underbelly within Christianity that comes out in weird places at weird times. This part isn't a specifically Catholic thing, you can see aspects of it peeking out from behind other sects as well. Christ as an aspirational figure, absent his specific historical context, kind of makes pain and martyrdom aspirational for essentially their own sake. And, when you remember that Christianity is also a strongly evangelical religion, well...how best to sanctify and elevate the masses?

The torture of suspected heretics during the Spanish Inquisition was referred to as auto de fe, the "act of faith." The specific act most often associated with this label was the public burning to death of heretics on a pyre, surrounded by chanting parishioners.

Recent addition to the roster of saints Mother Teresa is known to have avoided and discouraged the use of painkillers in her charitable medical work. For the explicit reason that the suffering of the patients would bring them closer to God.

During the Christianization of Europe, there was a frequent practice of forcing captured pagan leaders to convert before executing them. The official rationale being that doing so would ensure their souls reached heaven. But the actual sequence of actions being performed - the ritual words, the sacraments, and then the execution - falls very neatly within another type of religious practice that people throughout time and space have independently reinvented.

...

The church is its membership. The church is the body of Christ. The suffering of Christ is desirable. Salvation is attained by eating Christ's flesh and drinking his blood.

...

During the Inquisition era, why was it so important to make the sacrificial victims Christian before offering them up upon the pyre? Because that's how the ritual works. They need to become the flesh of Christ in order that their suffering and death be made sacred, and their blood made his own in order to grant eternal life when the church drinks it. Think of it as another kind of transubstantiation

...

Once again, I will say that I can't vouch for the historicity of all of these critiques of Catholicism (and Christianity more broadly). Some of them, but not all. So take this with a grain of salt.

Additionally, even my lapsed Catholic friends who I'm getting this from don't believe that this is a conspiracy or anything. Nobody in the early church intended this. It's just an unfortunate result of conceptual overlap, historical circumstances, and the human tendency to fall into certain patterns of belief when given the right prompting.

That said, if you look at the most reactionary, fascistic type of tradcaths, you will find people who believe at least most of this consciously. Looking through Christian history, there's a smattering of similar cases, concentrated in the church's most bellicose eras. A logic within the doctrine that's always waiting to be put into practice.

The church of christ. The vampire.