Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance (pt. 21)

From Armstrong's death, we go to the Maverick crew watching a newscast, seemingly a few months later. Courtney is calling bullshit on how the fallout of the event has played out, and so am I.

How much more evidence of that attack being a false flag would you need?

If the news media and federal government are just 100% in the pocket of the warmongers then I could buy this. But if that were the case, Armstrong shouldn't have needed to do a false flag in the first place.

The worst outcome seems to have been prevented, at least. The US is going to start doing operations against the Pakistani rebels, but at least they're working with the Pakistani government instead of against it, and the chances of it ballooning out into a regional conflict a la the first War on Terror seem to be lower. PMC's, including the remnants of World Martial, are still getting an uptick in employment because of this, but at least Armstrong isn't there to make everything worse just for its own sake.

They start talking about Raiden's fate, but are cut off by a call from Doktor with an update about their new venture. Maverick, in cooperation with Doktor's chronically unnamed company, is going to start moving from security services to general employment. Specifically, they're trying to encourage integration of cyborgs into civilian life and get them working in nonmilitary fields where their augmentations can still work in their favor.

I still don't understand why this was a problem to begin with. Even if most cyborgs underwent the change for military purposes, the assertion that society hasn't been allowing them to do anything besides that afterward is one that really needed to be explored and explained more than it was. Still, taking the world of the story at face value, they're doing a good thing.

Doktor in particular says that recent events had him rethinking the whole concept of "ethical" mercenary work. With how he presented himself in the game's earliest conversations, I wonder if it's less a change of heart and more being spurred into action. Like the cynicism was just the defence mechanism of a man who'd given up hope that the world could be better than this, but now has been galvanized into dropping it by the threat of it being made even worse.

Boris enters the room, and says that there's self-interest involved here as well. No one else is willing to take all the brains they rescued, and they can't afford to keep them all embodied pro bono. So, they're helping the World Martial victims learn marketable skills and get jobs. Some of them are old enough to be legally employed, on a part time if not full time basis. The rest of them will be soon enough, and teaching them to do industrial stuff that only a cyborg could do should help their prospects and also let Maverick take a cut.

Definitely a more optimistic ending than I'd expected.

Cut to Solis headquarters, where general assistant George is settling into his new employment using his half-cyborg body to move heavy objects around for Sunny. Who he has a crush on, and who might just reciprocate. Daaaaw. Also, she's adopted Pochita. Even more daaaaaaaaw.

Kinda wish these two were in the story a bit more, but I guess giving them any more screentime would have taken more contrivance than it's worth.

I wonder what Pochita's status is, legally, professionally, and socially? What is he going to aspire to now that he's (as far as I can tell) free from a life of war? For now, he just seems to be lazing around Sunny's office. And maybe that's all he needs to do for now. Take some time off just thinking and learning how to be himself. Whatever that ends up meaning.

After the three of them are done being cute, they turn the conversation topic to Raiden. Both of them were rescued from fates worse than death by him, either in this game or a previous one. And, while Sunny knows that he's a deeply flawed and deeply violent individual, she doesn't believe that he's just Jack the Ripper like some people say. The Raiden she knows is a hero, whatever other bad things he might also be or have been.

Then we have one last, very final scene. Raiden having a phone chat with Boris, seemingly in his Jack the Ripper persona. Raiden hasn't come back to Maverick (not that he probably can, given his criminal status at this point), and the two haven't seen each other in person for quite a while (possibly not since the events of the game, though granted he probably played a role in getting Pochita back to the USA so on second thoughts maybe not). World Martial is still out there, even after being essentially cored. Which is bad, Raiden says, because that means more PMC's fighting for causes they don't really believe in. He, meanwhile, has his own war to fight.

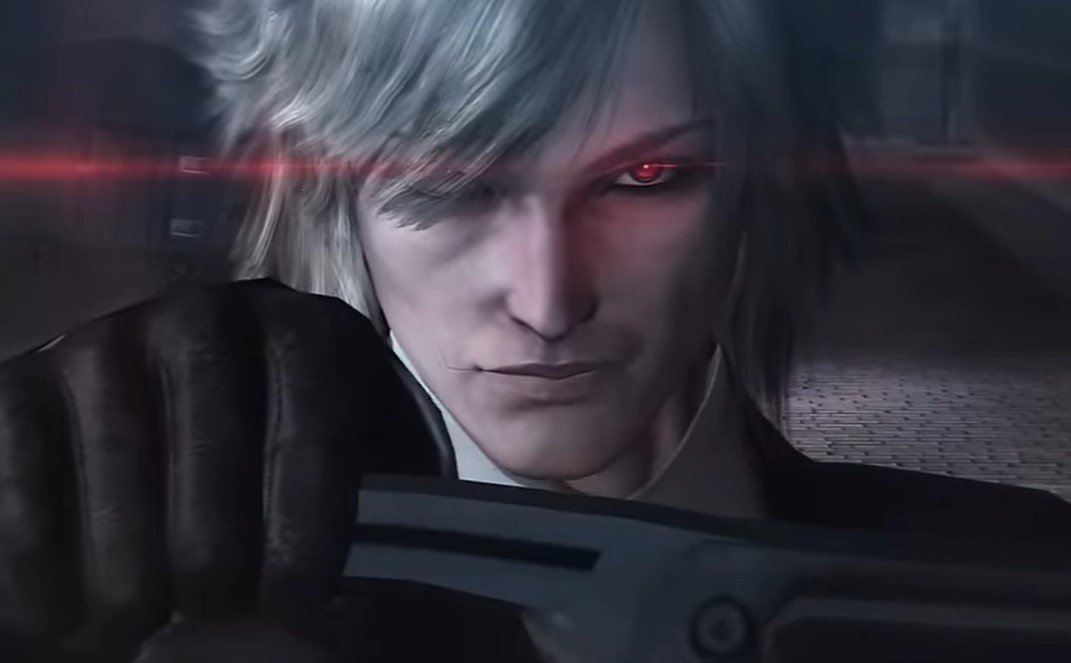

We see that Raiden is in a dark alley being surrounded by WM-looking cyborgs. He draw-flourishes his cyberkatana, and looks at the camera like this:

Roll credits.

I don't know how to read that ending.

The most obvious meaning is that Raiden was corrupted by his experiences with Armstrong and Co and is now working on the same batshit line of reasoning as them, while indulging in the bloodlust he was never able to shake off from his childhood. That this game is a villain origin story, a tragedy of Raiden's weakness and gullibility bringing him down into the abyss again and setting him up as the bad guy for a potential future sequel. That Sunny's looking up to him for the good that he's done, thus positioning her to be an accomplice to whatever evil he does next (and perhaps eventually forgetting how to talk and learning how to breathe through her skin), is just yet another tragedy.

If this is the route he's going, then that just seems...unfair. Raiden going off the grid after the Mexico mission and fighting a one man war for his own convictions seems to have had nothing but positive results. The Pakistan war is still happening, but it won't be nearly as bad (and it still happening at all is just down to Raiden's raid on WM having unfortunate timing, more or less). The orphans have been rescued, and are - along with Raiden's old coworkers - being set on the path to the happiest, most productive, least violent lives they can probably still have. Raiden never really crossed any moral lines as a result of him rediscovering Jack the Ripper; even in his Ripper persona, with the derpy voice and everything, he still avoided harming people who weren't putting themselves in his way, and the game encourages the player to rescue additional civilians even besides the orphans he personally empathizes with. He was using the Jack the Ripper bloodlust as a source of strength, but he also seemed to have it pretty well under control.

Has that changed now, as a result of exposure to Armstrong's nonsense? Has Raiden fallen for that nonsense and started crossing moral lines he wouldn't have crossed previously, working toward an incoherent vision of individualistic brutality for everyone? Or is he just stopping another evil plot from World Martial's remnants using the same means he was using before? He LOOKS all evil in the ending shot, but he's looked all evil while not really doing evil before. What is he actually doing now?

It's also possible that the game isn't intending Raiden to be a bad guy now, and the stinger was just a "the adventure continues" hook. Maybe he was repurposing Armstrong's "people fighting for causes they don't believe in" line to refer to the PMC industry as epitomized by World Martial specifically, rather than the more generalized and less sane way Armstrong meant it. In particular, I'm also thinking about Courtney's line in the Maverick ending scene, about imperfect solutions for an imperfect world. Maybe for Raiden to be at his most effective, he needs to draw on his bloodlust and love of violence for its own sake while still making sure to turn it toward positive applications. That definitely fits the tone of the preceding scenes much better, but tone is not remotely a reliable indicator of message in this series. Also, in this case, Raiden attributing his continued positive actions to a version of Armstrong's philosophy is REALLY dignifying the latter unduly.

The symbolism of only Sam's sword being able to hurt Armstrong is also...I don't know. It could be saying that Raiden, specifically, needs to use his own blood knight tendencies to his advantage in order to fight against the type of evil that gave him them. It could also be saying that the only way to fight this type of evil is to become it, that war is an inescapable ouroboros that is absolutely corrupting but also necessary to defend against the preexisting corruption, and that everything sucks forever no matter what. I don't want that to be the message, but that doesn't necessarily mean that it isn't the message.

Well, that's the end.

Thoughts on this game as a whole. Hmm.

I'm not sure which phrasing would be more accurate: "it's good, but it's a mess," or "it's a mess, but it's good." For a lot of it, "it's good BECAUSE it's a mess" might actually be more like it. The jank is a huge source of charm. Like I think I said in an earlier post, MGRR is an intricate mixture of "so bad it's good" with "unironically good," and only the occasional bit of "just bad."

It makes me wonder about the previous versions of the game that ended up being synthesized into this one. Did they, at least in part because of the awkwardness of their synthesis, combine into something better than the sum of its parts? Or, is MGR:R just a pale reflection of the one or two better and more consistent games that never got made? We'll never know.

...

As far as gameplay goes: I don't like fighting games, especially spectacle fighters. I also don't like the love affair that gaming had with QTE's in the late aughts and early tens. The fact that I enjoyed the majority of MGR:R's gameplay as much as I did, and that it actually gave me a bit more appreciation for its genre than I had before, is a testament to its quality. Not my jam, but a very high quality jam that I can enjoy even though it's not mine.

If I played this game as it was meant to be played, with a controller, it might have improved my opinion of fighting games further still. If I ever get a decent gaming setup, I'll have to give it a replay and see.

Genre aside, there are some principles of game design that are near-universal, and Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance does a hell of a lot of things right. The xp and upgrade system is perfectly paced. The wide range of tactics and approaches each fight allows the player to choose makes it much more replayable than most ultra-linear games. And really, just the strength of the zandatsu mechanic being the core of the player character's survivability, the rewarding of forward momentum with the ability to move forward even further, is damned near perfect. I'd really like to see games of other genres do something similar to this.

I'm thinking about my first comment on how Raiden plays, back in the first post, about how he handles more like a typical videogame boss than a typical videogame protagonist. The rest of it all kind of builds up and around from that core, what with the invincibility phases, vulnerability to stunning, and glowing red danger mode. Makes me wonder about the way playable versus antagonistic game characters are usually designed, and whether gaming could benefit from those conventions being stirred up in other ways too.

As I've noted throughout this playthrough, MGRR's weakest gameplay bits are uniformly the ones where it doesn't let itself be itself. The (often weirdly placed and weirdly paced) shifts into fixed perspective quicktime gauntlets. The invisible walls that (at least in some cases) only exist to make a fight harder at the cost of the game's usual enjoyable freedom of movement. Mixing up gameplay modes here and there is important, but I feel like MGRR often did so in a way that worked against its own strengths. I blame this mostly on the era the game came out in, that shit was ubiquitous at the time.

On the topic of linearity, and on how Revengeance's structure was kind of Frankenstein'd together from very different concepts and also very short for a triple-A release, I think that one thing a better planned out version of the game might have had is branching mission selections. Say, after the intro mission, the player is given a choice of what job Maverick should take next. Some of these missions end up exposing revelations about the Desperado/World Martial plot, while others just get you XP and equipment and provide more contextualizing info about the state of the world and thus more ability to understand how Armstrong plans to exploit it. If the World Martial raid was an unlockable endgame after you've done enough other missions, it would also let the game pace the Winds of Destruction fights much more evenly and let the robo versions of them in the tower be a more proper penultimate-level-boss-rush.

Obviously, this would have made it a much bigger game with much more development needed, and with the multiple setbacks it already had during creation asking for any more content is ridiculous. I'm just saying, hypothetically, a version of Revengeance that *didn't* have those production issues might have done well to go in this kind of direction.

...

The significance of the title, "revengeance," wasn't clear to me until the final fight, but now that I've beat the game - even if I don't know what the ending is supposed to mean exactly - I see the big picture of the story. Revenge not against a person (the individuals most responsible for harming Raiden were all killed, some of them by Raiden himself, in previous games), or even against an organization (he's not trying to bring down the United States, at least I don't think), but against a concept. Revenge against "war as a business." The military industrial complex as a category of institutions, and everyone responsible for propping it up. The late capitalist America-led version of it is just that; one version. As Armstrong demonstrated, it's possible to reject that particular manifestation while still clinging to the ethos that makes other versions of it inevitable.

I guess in that way, you could see Armstrong's last couple of speeches as a test of Raiden's judgement and character. Will he be hoodwinked into thinking he can defeat this monster while behaving exactly like it, or will he understand the dynamics behind the aesthetics? Or, rather, did he? The ambiguity of the ending makes it hard to say if Raiden passed or failed.

The game has a lot going on philosophically, as a whole, but a lot of it is sort of scattershot. The takedown of retributive justice as a concept (even just plain revenge is more worthy of respect than retributive justice, in the game's view, and it makes a solid case for this), and the hypocrisy with which broader society regards violence done on its behalf, was probably the strongest stuff. Right up there with that, of course, is the glory that was Armstrong's epitomization of rightwing madness beneath its pretentions of pragmatism, and the various pseudo-dignified excuses and masks that each of the Winds place over that festering heart. The stuff about the nature of violence itself, with the dubious effectiveness of the Sears program and the Jack the Ripper stuff, I'm much less impressed by; it kind of feels like the story is drinking the same Kool-Aid it wants to denounce with some of that. When it tries to comment on stuff like media manipulation and societal trends toward intolerance and the like (ie, everything about Operation Tecumseh, or the role of cyborgs outside of warfare) it mostly just faceplants.

It's one of those works where I'm not sure if you'll get more out of it by paying close attention and thinking about what it says, or by turning your brain off and just laughing at the funny parts and mashing the "hit robot with sword" button at all the other parts. It both rewards and punishes you for doing either of those things.

But like. All that aside. Moreso than anything else. Story, music, pacing, politics, all of it. The biggest takeaway from this game that I got, and probably the biggest one that anyone got, is that it's really, really fun to play. Really, it's core gameplay is enough of a draw that nothing else about it, for good or for ill, is nearly as meaningful by comparison.