The Promised Neverland #2-3: "The Way Out" and "A Declaration of War"

The next little stretch of story is something I'm very curious to see the anime adaptation of. In particular, to see how well they brought it to life with music voice acting, timing, etc. Because it has the potential to be either one of tensest and most powerful animated sequences ever, or to fall completely flat.

It's the next morning, and Ray, Norman, and Emma have to go through their day without letting Mom notice anything different about their behavior. Including their ambient level of cheer and enthusiasm, and the way they interact with her specifically. They don't just need to pretend that everything is fine; they need to make their behavior totally indistinguishable from how it was yesterday, at least while she might be watching.

The easy part is letting wishful thinking do the work. All three of them would dearly love to believe that last night was just a bad dream, so it's surprisingly easy to act as if it was.

The hard part is resisting the temptation to let themselves actually be convinced it was just a bad dream. Everything inside of them and surrounding them is trying to get them to do that.

Would three eleven year olds really be able to walk this emotional tightrope, neither embracing wilful ignorance nor letting the mask slip? Like I said before, I'm somewhat sceptical. Their ability to hit the ground running after such a revelation continues to be the most shonen-y aspect of this story. I'd attribute their success here more to Mom having almost forty other kids to keep track of than to them really pulling off a perfect performance, but the story later makes it explicit that she knows that two children saw last night's events and is testing them all in turn, so...these three just have superhuman emotional control I guess, heh.

They use their free time throughout the day to talk plans and investigate possible escape methods. Things they never questioned before seem altogether sinister now. The window latches and bolts are all on top; within reach for an adult, but not for even a tall child. The screws holding in the steel grates are all uniformly too rusty to remove, but not rusty enough to break. At least one of them is capable of picking the lock on the back door, but that still limits them to a single, easily-watched egress from the building. Their crisp white clothes reveal any mud, dust, iron filings, etc at a casual glance, making it impossible to hide what they've been up to if they try to dig or saw their way through something in stages. And above all else, Mom is just so unfailingly loving and supportive. The beds are so warm. The food is so tasty and plentiful. The will to keep believing in the truth gets harder and harder to maintain the more time passes.

It's a really uncomfortable observation on the measures we put in place to control children, pets, prisoners, and livestock. Specifically, how little difference there is beyond superficial comforts and aesthetics. The mechanisms to switch an entity between one class of social inferior and another are all already ubiquitously in place.

Granted, there are also some details that are more unusual on closer examination, and these help the trio remain dedicated and undeluded.

Norman raises a good point. An even better one than he realizes, in fact. Why are the children even allowed to know about things like radio communications? If they were brought here while they were still too young to have memories, why do they even need to be told that they're in an "orphanage" and will be eventually "adopted?" Why let them have so much unnecessary and potentially dangerous knowledge, especially when it could potentially lead them to notice the cracks?

It might be related to them being given such a rigorous math and logic education, with their test scores having significance for the consumer. Surprisingly, it's Norman rather than Ray who puts it together.

...actually, virtually everything so far has been Norman's idea or Norman's decision. Why are we following Emma, again?

...also, I just looked back at the end of chapter one, and I think I may have misinterpreted something. When they come back from the gatehouse, we see Norman and Emma meeting Ray and him asking wht has them so freaked out, and then we see Ray commenting on contradictions that always bothered him about the orphanage, but it seems like the latter might have been flashbacks. Or even Norman musing in the immediate wake of us seeing Ray. And in the following chapters, yeah, it's all Emma and Norman. Did they not tell Ray what they saw, after all? Maybe they didn't. Huh.

Well, tangents aside, Norman has a theory about their education. Emma helps him recall the order of adoptions during their time at Grace House, and there's a pattern.

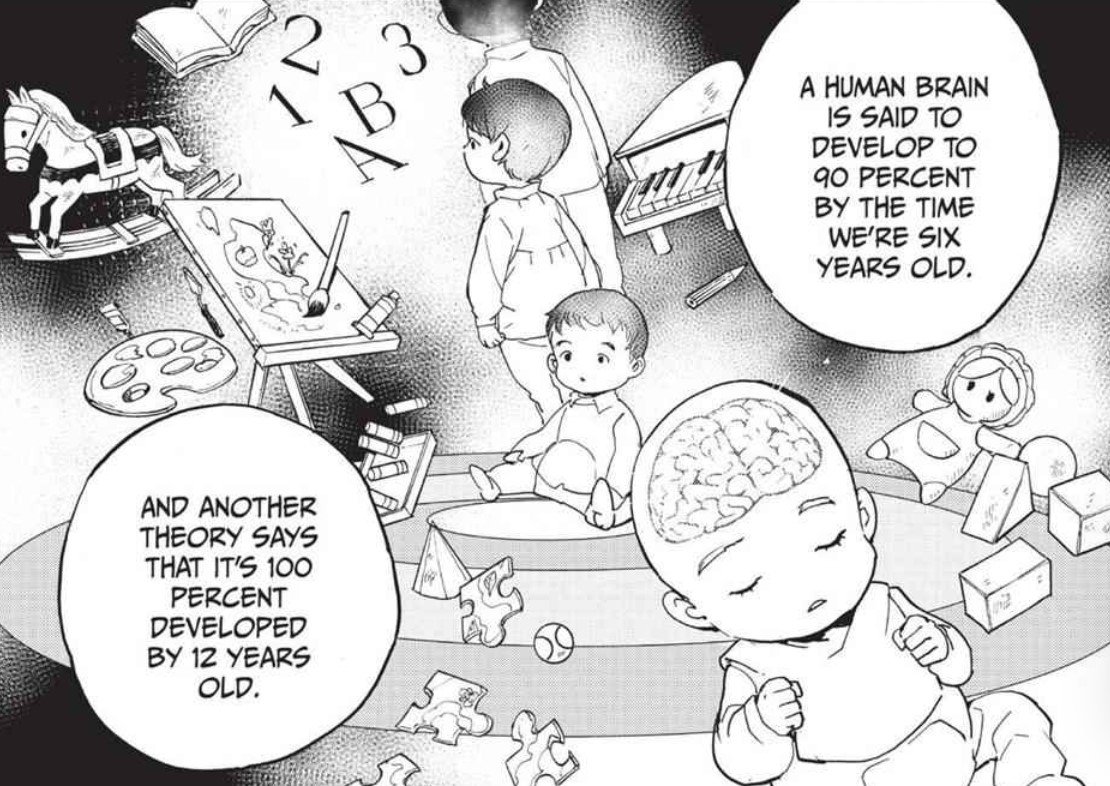

Which coincides with some pediatric trivia he happens to remember.

If it's the brains in particular they want, then it makes sense to get some of them ASAP while letting the best ones grow and develop some more to maximize their returns. More implicitly, this could explain why they're being given accurate general knowledge about at least certain aspects of the real world instead of being fed a total fantasy. If the demons need the brains to have information as well as complexity, then letting the kids know so much might be a necessary evil from their perspective.

A major assurance (not in the comforting sense, heh) that the danger is real comes when Norman and Emma sneak out passed the fence in the forest to see if there are barriers beyond the psychological. Turns out that there unfortunately are. The fence only exists to keep them from going far enough into the forest to see the 10 foot tall concave wall hidden behind the tree-tops.

Emma thinks she can get them over it with the help of the closer tree trunks, provided she had a rope. It's not at all clear if the younger children would be able to climb it, but the older ones probably all could. They really, really don't want to leave anyone behind, though. These "orphans," from the toddlers on up, are the only family that Norman and Emma have. With the shocking loss (effectively) of their one parental figure, they're even more precious to them than they were yesterday.

On the topic of said false mother, well. Over the next day or two, things start to escalate with her. On top of making a point of catching each kid alone in turn and asking them if there's anything bothering them - while putting a hand on them to feel their pulses as they answer - she takes an opportunity to get a little message out to whoever dropped that bunny in the gatehouse last night. That said...I have to wonder if the message is actually meant to communicate what Norman and Emma thinks it's meant to. That evening, a younger girl doesn't return from the woods in time for dinner. Mom sets out into the woods, and finds the girl (who'd fallen asleep under a tree) in under a minute. While returning with the child, she pointedly brandishes this old-fashioned pocketwatch in front of everyone before putting it away again.

GPS implants. That pocketwatch has to be a concealed receiver. And if she's suddenly being so unsubtle about it, Norman reasons, then she's probably doing so as a threat. "You can't escape me, so don't even try."

That said, she's still trying to figure out which kids it was. Which implies that while she can track the past movements of each chip, she doesn't have all three dozen of them individually labelled. Meaning she knows there were two kids who snuck into the gatehouse, but she doesn't know which too.

Where I think Norman might be misinterpreting her, though, is that it's possible Mom is trying to help them. Warning them about the tracking systems and the limitations thereof in the hopes that they can find a workaround without her needing to implicate herself.

Although, on the other hand, we do get inside of Mom's head a little when she's testing their pulses, and she does seem to be making a serious effort then.

The scene where she tries to get Emma to crack is the tensest and most difficult-to-read scene of the first three issues, by the way. Emma thinking about all the betrayal, all the insincere performance of love maintained immaculately over the course of so many years. She feels sick. Wants to cry and scream and pass out all at once. But, somehow, she doesn't crack.

Mother's smiles and body language also have subtle changes between the first issue and the latter two. The artist putting just suuuuubtle little adjustments in to make her maternal expressions look like barely-suppressed sinister grins, and her parental authority come across as monstrous size and power.

The righthand panel, centering her body from a low-angle to make her look like a literal giant.

At the end of issue three, we get confirmation that Mom (or Isabella, as we learn her name is) isn't softballing. Or, if she is, she's doing it through unconscious self-sabotage rather than intentionally trying to help them. She isn't a disguised demon, it turns out, which gives her a very strong motive for wanting to run a tight ship.

I'm honestly not sure if her being human makes her slightly less of a monster, or slightly more of one.

It also makes the kids' prospects even bleaker. It seems like the demons have conquered the world, or at least the region, and all humans under their regime are either food or Judas goats. Most of them probably living in much, much worse conditions than those at Grace House.

Also, unless they can figure out where the chips are embedded and cut them out of their bodies, no escape will last even if they had anyplace to escape to. Isabella most certainly isn't the only one who can track those chips.

Based on the rate of "adoptions," Emma and Norman estimate that they have - at most - two months to figure this out.

The manga goes for 182 issues, and I don't think these children are decoy protagonists, so they must end up surviving somehow. I really don't know how, though.

Anyway. Definitely something, this comic. Something.

The Promised Neverland is less than a decade old, but I think I've already seen its influence in more recent Japanese media. "Shadows House" probably wouldn't exist (or at least would be very different) were it not for TPN. I feel like some of Fujimoto's work might also have been influenced by it, though he was already covering at least some of the same ground as early as 2011 with his "Kickin' Chickens" short. I think we're going to continue seeing its influence for some time yet.

The comic is still trying to find its footing in terms of characters, I think. The weird imbalance of plot importance and narrative attention between Emma and Norman (and Ray? maybe?) in particular smacks of a story still figuring itself out. That said, I very much enjoy the kind of deductive reasoning the story has the kids employ to deal with the situation at hand. Really good depiction of genuine brilliance rather than Hollywood Genius at work. It just needs to balance it a little better.

More than anything though, it's a nightmare that you'll probably have again repeatedly after you've read it.